5. Milk for all: A Clockwork Orange and The Edible Woman

Margaret Atwood’s The

Edible Woman –

‘The infant’s earliest experience of the human female

defines her as literally consumable.’

(Smith 86)

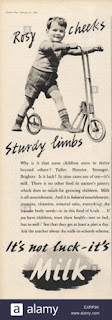

The ideology surrounding vitality attributed to the consumption of cow’s milk

permeated the post-war decades, including the 1960s, in which A Clockwork Orange was published. In the

1940s, 1950s and 1960s, Western advertisements of the importance of the

inclusion of milk in the diet were featured. The advertisements portrayed men

and women of all ages with claims that one will ‘feel a lot better if [they]

drink more Milk’, or to ensure children will grow ‘sturdy limbs’ with adequate

milk consumption.

Although this milk advertising is targeted at adult men and women for both themselves and their children, it is relevant to note that the descriptions seem to suggest that by drinking this milk, adults will be restored with ‘vigour’ and health, meaning that the ‘nourishment’ from this drink will help you to return to a youthful state; ‘recharged’ and ‘refreshed’. The claims made of the restorative qualities of the apparent superfood evoke connotations of a mother’s human breast milk to a nursing child. The claims of a childlike new-found energy suggest an adult desire to return to an infantile state, nursed and regenerated by wholesome milk. As the maternal figure must care for her husband and children, it is relied upon her to ensure they drink milk as it contains healthy properties.

Although this milk advertising is targeted at adult men and women for both themselves and their children, it is relevant to note that the descriptions seem to suggest that by drinking this milk, adults will be restored with ‘vigour’ and health, meaning that the ‘nourishment’ from this drink will help you to return to a youthful state; ‘recharged’ and ‘refreshed’. The claims made of the restorative qualities of the apparent superfood evoke connotations of a mother’s human breast milk to a nursing child. The claims of a childlike new-found energy suggest an adult desire to return to an infantile state, nursed and regenerated by wholesome milk. As the maternal figure must care for her husband and children, it is relied upon her to ensure they drink milk as it contains healthy properties.

This contemporary view of milk as a restorer might have

influenced Burgess in his novel, A

Clockwork Orange. Youthful characters drink ‘milk-plus’ (Burgess 11): milk spiked with drugs. The milk, or ‘moloko’

(38), is abundant in this text, and the male characters can be found at the

Korova Milkbar each night, ‘making up [their] rassoodocks [minds] what to do

with the evening’ (Burgess 11). In the decades preceding this novel, milk was

aggressively marketed as an extremely healthy drink that is essential to our

diet. Burgess may have been satirising the propaganda-style of milk advertising,

as it claims to heal through its pure healthiness.

Alex describes their preferred drink as ‘milk plus something else’ (Burgess 11), meaning that the milk makes up a large portion of the mixture, with the enigmatic ‘something else’ as a small fraction of the drink. This seemingly presents milk as a more important factor of the mix, or less potent component, emphasising the safety of the milk; akin to the security of breast milk.

The contemporary caring and ideal mother figure would feed

milk to their children with the belief that it will ensure they grow into strong

and healthy adults. The youth of this novel buy it themselves from a Milkbar,

in which they drink ‘milk with knives in it…and this would sharpen [them] up and

make [them] ready for a bit of dirty twenty-to-one’ (Burgess 11). Dirty

twenty-to-one is likely to be gang violence, and the metaphor of knives within

milk is disturbing and subverts the contemporary belief of its health benefits.

I argue that Burgess might have endeavoured to state the importance of a

caring, maternal role of a mother feeding her child compared with the dangers

of milk that she does not supply. This connotes a breastfeeding mother, and a

possible unconscious desire for maternal influence from the young men.

The milk and drug concoctions are seemingly complementary; Alex

explains that upon drinking, it ‘would give you a nice quiet horrorshow [good]

fifteen minutes admiring Bog [God] And All His Holy Angels And Saints in your

left shoe’ (Burgess 11). The religious imagery, witnessed after the milk

consumption, could relate to ‘the Madonna and child, our most pervasive iconic

image’ (Smith 86) of a son with his mother. The iconic maternal figure of Mary

with her son Jesus presents the ultimate ideal of a mother nurturing her child.

Burgess had a ‘Catholic conscience’ (Walsh), meaning the inclusion of Christian

deities could reflect his own religious views.

The milk can cause those who drink it to encounter God and

‘lights’, or knives and violence. These juxtaposing images could suggest

Burgess’ opinion of a new God-less, mother-less and immoral society, as we can

choose to experience the caring, maternal nature of our omnibenevolent God, or

reject this in favour of satanic, youthful violence.

The Edible Woman

features a male character, Len, that denotes infantilism in the way he consumes

beer, a stereotypically masculine drink, with the ‘squat brown bottle’

upturned, and his ‘mouth pursed budlike around the bottleneck’ (Atwood 156). The

beer may represent milk, as he drinks from the bottle in a strikingly infantile

manner. The use of his mouth as a bud further suggests youth, as a bud of a

flower is young, new and undeveloped. He has very recently been told of his

pending fatherhood, in which he had not given his consent; Len is unaware of

the intentions of his sexual partner, as she sought to become pregnant without

his knowledge, nor does she ‘want a husband’ (157). His reaction to this news

is immature; Marian ‘felt as though she should take him upon her knee and say,

“Now Leonard, it’s high time I told you about the facts of life”’ (157). His

return to an infant-like state shows a dependence on the care of a mothering woman.

Both men and babies share the ‘need’ of care from a woman as a wife or mother. Babies

drink greedily; it is the feminine duty to reserve delicacy for a baby and her

husband. Atwood could be commenting on the infantile state of contemporary

masculinity and impulsiveness, as women were expected to efficiently prepare

for their sensitivity and clumsiness. Len, an adult male, ‘gave a small gurgle’

(157) after swallowing this beer. A gurgle is an unmistakable childish sound of

indigestion, which could represent his bodily rejection of his impending

fatherhood by regressing to a child-like state himself.

Elderly Man and Woman Drinking Milk

1940s Advertisement. Advertising Archives,http://www.advertisingarchives.co.uk/detail/31713/1/Magazine-Advert/Milk-Marketing-Board/1940s

”1950s UK Milk Magazine

Advert.” Alamy, The Advertising Archives and Alamy Stock

Photo, https://www.alamy.com/mediacomp/imagedetails.aspx?ref=EXRP2K&_ga=2.22412219.1450612303.1543167471-1369421785.1543167471.

”Original 1950s vintage old print

advertisement from English magazine advertising Drink More Milk circa

1954.” Alamy, f8 Archive and Alamy Stock Photo, 1954, https://www.alamy.com/original-1950s-vintage-old-print-advertisement-from-english-magazine-advertising-drink-more-milk-circa-1954-image225383206.html?pv=1&stamp=2&imageid=BE2E7851-179F-4845-B901-D5C7E5478293&p=164363&n=0&orientation=2&pn=1&searchtype=0&IsFromSearch=1&srch=foo%3dbar%26st%3d0%26pn%3d1%26ps%3d100%26sortby%3d2%26resultview%3dsortbyPopular%26npgs%3d0%26qt%3dmilk%2520advert%26qt_raw%3dmilk%2520advert%26lic%3d3%26mr%3d0%26pr%3d0%26ot%3d2%26creative%3d%26ag%3d0%26hc%3d0%26pc%3d%26blackwhite%3d%26cutout%3d%26tbar%3d1%26et%3d0x000000000000000000000%26vp%3d0%26loc%3d2%26imgt%3d0%26dtfr%3d%26dtto%3d%26size%3d0xFF%26archive%3d1%26groupid%3d%26pseudoid%3d%26a%3d%26cdid%3d%26cdsrt%3d%26name%3d%26qn%3d%26apalib%3d%26apalic%3d%26lightbox%3d%26gname%3d%26gtype%3d%26xstx%3d0%26simid%3d%26saveQry%3d%26editorial%3d1%26nu%3d%26t%3d%26edoptin%3d%26customgeoip%3d%26cap%3d1%26cbstore%3d1%26vd%3d0%26lb%3d%26fi%3d2%26edrf%3d0%26ispremium%3d1%26flip%3d0%26pl%3d

Comments

Post a Comment